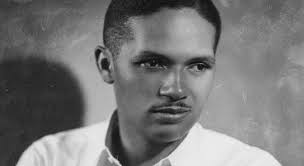

I'm Shirley Griffith. And I'm Rich Kleinfeldt with the VOA Special English program PEOPLE IN AMERICA. Today we tell the story of Todd Duncan -- a concert singer and music teacher. He is the man who broke a major color barrier for black singers of classical music.

It is nineteen-forty-five. The place is New York City. The New York City Opera Company just finished performing the Italian opera "Pagliacci."

Todd Duncan is on the stage. He had just become the first African American man to sing with this important American opera company. No one was sure how he would be received. But the people in the theater offered loud, warm approval of his performance.

Duncan did not sing a part written for a black man. Instead, he played a part traditionally sung by a white man. All the other singers in the New York City Opera Company production were white.

His historic performance took place ten years before black singer Marian Anderson performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Todd Duncan opened doors for other black musicians when he appeared in "Pagliacci." Until that night, black singers of classical music had almost no chance of performing in major American opera houses and theaters. But Todd Duncan began a major change in classical musical performance in the United States.

Todd Duncan lived a very long life. He was ninety-five years old when he died in March, nineteen-ninety-eight in Washington, D.C. He taught singing until the end of his life.

Robert Todd Duncan was born in nineteen-oh-three in the southern city of Danville, Kentucky. His mother, Nettie Cooper Duncan, was his first music teacher.

As a young adult, he continued his music studies in Indianapolis, Indiana. He attended both a university and a special music college in this middle western city.

In nineteen-thirty, he completed more musical education at Columbia University in New York City. Then he moved to Washington. For fifteen years, he taught music at Howard University in Washington.

African Americans had gained worldwide fame for their work in popular music -- especially for creating jazz. But not many black musicians were known for writing or performing classical music.

Teaching at Howard gave Duncan the chance to share his knowledge of classical European music with a mainly black student population. He taught special ways to present the music. These special ways became known as the Duncan Technique.

Here Todd Duncan sings "O Tixo, Tixo, Help Me" from the opera "Lost in the Stars" composed by Kurt Weill.

In addition to teaching, Duncan sang in several operas with performers who all were black. But it seemed he always would be known mainly as a concert artist. Duncan sang at least five-thousand concerts in fifty countries during twenty-five years as a performer.

However, his life took a different turn in the middle nineteen-thirties. At that time, the famous American music writer George Gershwin was looking for someone to play a leading part in his new work, "Porgy and Bess."

Gershwin had heard one-hundred baritones attempt the part. He did not want any of them. Then, the music critic of the New York Times newspaper suggested Todd Duncan.

Duncan almost decided not to try for the part. But he changed his mind. He sang a piece from an Italian opera for Gershwin. He had sung only a few minutes when Gershwin offered him the part. But Duncan was not sure that playing Porgy would be right for him.

Years later, he admitted that he had no idea that George Gershwin was such a successful composer. And, he thought Gershwin wrote only popular music. Duncan almost always had sung classical works, by composers such as Brahms and Schumann.

Todd Duncan said he would have to hear "Porgy and Bess." He did. Then he accepted the part of Porgy. But he said he found it difficult to perform because Porgy has a bad leg and cannot walk. He spends most of the opera on his knees.

Duncan used his special methods to get enough breath to produce beautiful sound. He was able to do this even in the difficult positions demanded by the part.

Here Todd Duncan sings "Porgy's Lament" from the Gershwin opera, "Porgy and Bess."

Todd Duncan sang in the opening production of "Porgy and Bess" in nineteen thirty-five. Then he appeared again as Porgy in nineteen-thirty-seven and nineteen-forty-two. He often commented on the fact that he was best known for a part he played for only three years.

His fame as Porgy helped him get the part in "Pagliacci" with the New York City Opera Company. He also sang other parts with the opera company.

Earlier, you heard him sing a song from one of the operas he enjoyed most. The part was that of Stephen Khumalo in "Lost in the Stars." It was a musical version of the famous novel about Africa, "Cry, the Beloved Country" by Alan Paton.

American writer Maxwell Anderson wrote the words for the music by German composer Kurt Weill. Listen as Todd Duncan sings the title song from "Lost in the Stars."

Todd Duncan gained fame as an opera singer and concert artist. But his greatest love in music was teaching. When he stopped teaching at Howard, he continued giving singing lessons in his Washington home until the week before his death.

He taught hundreds of students over the years. Some musicians say they always can recognize students of Todd Duncan. They say people he taught demonstrate his special methods of singing.

Donald Boothman is a singer and singing teacher from the eastern state of Massachusetts. He began studying with Todd Duncan in the nineteen-fifties.

Boothman was twenty-two years old at the time. He was a member of the official singing group of the United States Air Force. He had studied music in college. But he studied with Duncan to improve his singing.

Boothman continued weekly lessons with Duncan for thirteen years. After that, he would return to Duncan each time he accepted a new musical project.

He says he considered Duncan his teacher for a lifetime. Many other students say they felt that way, too.

Todd Duncan was proud of his students. He was proud of his performances of classical music. And, he was proud of being the first African-American to break the color barrier in a major opera house.

He noted in a V-O-A broadcast in Nineteen-Ninety that blacks are singing in opera houses all over America. "I am happy," he said, "that I was the first one to open the door -- to let everyone know we could all do it."