I'm Shirley Griffith. And I'm Ray Freeman with the VOA Special English program People in America. Every week at this time we tell the story of someone important in the history of the United States. Today we tell about explorer, John Wesley Powell. He was also a scientist, land reformer, and supporter of native American rights.

The date is May twenty-fourth, eighteen sixty-nine. The place is Green River, Wyoming, in the western United States. The Green

River flows in a curving path south through Utah and Colorado until it joins the great Colorado River.

The Colorado, in turn, flows through a huge deep canyon. Years from now, that formation will be called the Grand Canyon.

Ten men are putting supplies and scientific equipment into four small boats.

They are about to leave on a dangerous, exciting exploration. The leader of the group is John Wesley Powell.

Powell writes in his journal: "The good people of Green River City turn out to see us start. We raise our little flag, push the boats from shore, and the current carries us down. Wild emptiness is stretched out before me. Yet there is a beauty in the picture."

So begins John Wesley Powell's story of his trip on the Green and Colorado Rivers. It was one of the greatest trips of discovery in the history of North America. He and his men were the first whites to travel in that area. Until then, the land had been known only to Indians and prehistoric tribes.

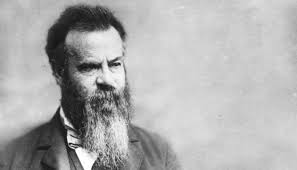

John Wesley Powell was thirty-five-years-old. He had served in the American Civil War. He had lost an arm in that war. He was an unknown scientist, temporarily away from his job at a museum in Illinois.

John's parents had come to the United States from England. They settled in New York State, where John was born in eighteen thirty-four. They later moved to Ohio. Mister Powell made clothes for other people, and farmed a little, too. He also taught religion. His teaching duties often took him away from home. Missus Powell believed young john needed the guidance and protection of a man. So she asked a friend, George Crookham, for help.

George Crookham was a rich farmer. He also was a self-taught scientist. He kept a small museum at his home. It contained examples of plants and minerals. Native animals and insects. Remains of Indian tools and weapons.

From George Crookham, John Wesley Powell received a wide, but informal, education. The boy learned many things about the natural sciences, philosophy and history.

In eighteen forty-six, the Powell family moved again. This time, they settled even farther west, in Wisconsin. John wanted to go to school to study science. His father said that if John were to be sent to college, it would be to study religion...not something as unimportant as science.

The argument continued for three years. Then John decided to leave home to seek an education.

He soon discovered that he knew more about science than any teacher he met. He realized that the only good scientific education in the country came from colleges in the east, like Harvard and Yale. But he was too poor to go to them.

John Wesley Powell got work as a school teacher in Illinois. Whenever possible, he went on scientific trips of his own.

In April, eighteen sixty-one, civil war broke out in the United States. John joined the Union forces of the North. At the battle of Shiloh, a cannon ball struck him in the right arm. The arm could not be saved.

Although John was disabled, he returned to active duty under General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant would later serve as Secretary of War and President. Powell's friendship with Grant would help win him support for his explorations of the west.

After the war, John Wesley Powell taught science at two universities in Illinois. He also helped establish the Illinois Historical Society. He urged state lawmakers to provide more money for the Society's museum. His efforts were so successful that he was given responsibility for the museum's collections.

One of the first things he did after getting the job was to plan an exploration of the Rocky Mountains.

Powell got help from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian gave him scientific equipment. He got help from the army. The army promised to protect the explorers in dangerous areas. And he got help from the railroads. The railroads agreed to let the explorers ride free as far as possible.

Powell's group brought back enough information to satisfy those who supported it. A second, similar trip took place the following year. Then Powell centered his efforts on the plan that would make him famous: exploration of the Green River and the Colorado River.

It was a voyage never attempted by white men. Indians who knew the area said it could not be done. But John Wesley Powell believed it could. And he believed it would provide a wealth of scientific information about that part of America.

Once again, Powell turned for help to the Smithsonian, the army and the railroads. He got what he wanted.

The explorers left Green River, Wyoming, on May twenty-fourth, eighteen-sixty-nine. All along the way, Powell measured distances, temperatures, heights, depths and currents. He examined soils, rocks and plant life. Since the explorers were mapping unknown territory, they named the places they passed as they went along.

The trip was just as dangerous as expected, perhaps more. The rivers were filled with rocky areas and waterfalls. Sometimes, the boats overturned. One of the boats broke in two against a big rock. The explorers suffered from a hot sun, and cold rain. They lost many of their supplies. Yet they pushed on.

On August thirteenth, eighteen-sixty-nine, they reached the mouth of a great canyon. Its walls rose more than a kilometer above them. Powell wrote in his journal:

"We are now ready to start on our way down the great unknown.

What waterfalls there are, we know not. What rocks lie in the River, we know not. We may imagine many things. The men talk as happily as ever. But to me, there is a darkness to the joy."

The trip through the great canyon was much the same as the earlier part of the trip. For a time, the Colorado River widened. The explorers were able to travel long distances each day. Then the canyon walls closed in again. Once more, the group battled rapids, rocks and waterfalls.

Conditions grew so bad that three of the men left to try to reach civilization overland. Two days later, the rest of the group sailed out of the dangers of the Grand Canyon.

The story of the brave explorers was printed in newspapers all over the country. John Wesley Powell became famous.

Powell's explorations led to the creation of the United States Geological Survey in eighteen seventy-nine. The survey became responsible for all mapping and scientific programs of American lands.

Powell's interests, however, were becoming wider than just the geology of the land. He found himself growing deeply interested in the people who lived on the land. On every future trip, he visited Indian villages. He talked to the people, and learned about their culture and history. He helped establish a bureau of American ethnology within the Smithsonian Institution to collect information about the Indian cultures. Powell headed the bureau for more than twenty years.

In a message to Congress, Powell explained why he felt the bureau was so important:

"Many of the difficulties between white men and Indians are unnecessary, and are caused by our lack of knowledge relating to the Indians themselves. The failure to recognize this fact has brought great trouble to our management of the Indians."

John Wesley Powell's scientific studies of western lands shaped his ideas of how those lands should be used. He proposed programs to control both crop farming and cattle raising. He was especially concerned about water supplies.

Many of John Wesley Powell's ideas were far ahead of his time.

Congress rejected Powell's proposals for land and water use. He died in nineteen-oh-two. Years later his ideas were signed into law.