In the beginning Rutherford worked on radio waves, and with some distinction—he managed to transmit a crisp signal more than a mile, a very reasonable achievement for the time—but gave it up when he was persuaded by a senior colleague that radio had little future. On the whole, however, Rutherford didn't thrive at the Cavendish. After three years there, feeling he was going nowhere, he took a post at McGill University in Montreal, and there he began his long and steady rise to greatness. By the time he received his Nobel Prize (for "investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances," according to the official citation) he had moved on to Manchester University, and it was there, in fact, that he would do his most important work in determining the structure and nature of the atom.

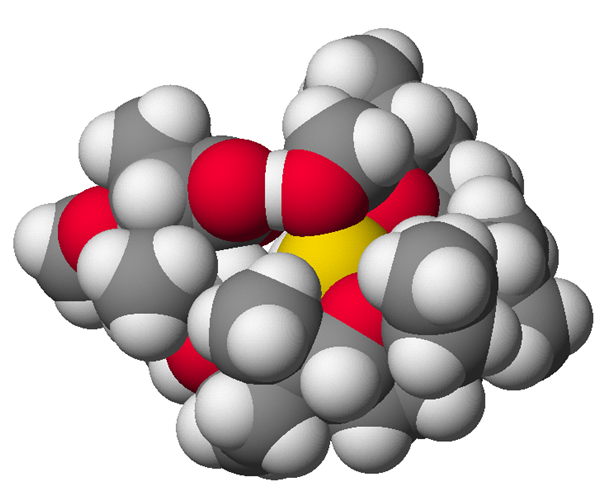

By the early twentieth century it was known that atoms were made of parts—Thomson's discovery of the electron had established that—but it wasn't known how many parts there were or how they fit together or what shape they took. Some physicists thought that atoms might be cube shaped, because cubes can be packed together so neatly without any wasted space. The more general view, however, was that an atom was more like a currant bun or a plum pudding: a dense, solid object that carried a positive charge but that was studded with negatively charged electrons, like the currants in a currant bun.