It is now thought that the larvae of certain organisms may drift through the water until, by some unknown chemical means, they detect that they have arrived at a food opportunity and fall onto it.

现在认为,某些生物的幼体可能在水里漂动,最后由于未知的化学原因,它们发现来了进食的机会,于是就扑了上去。

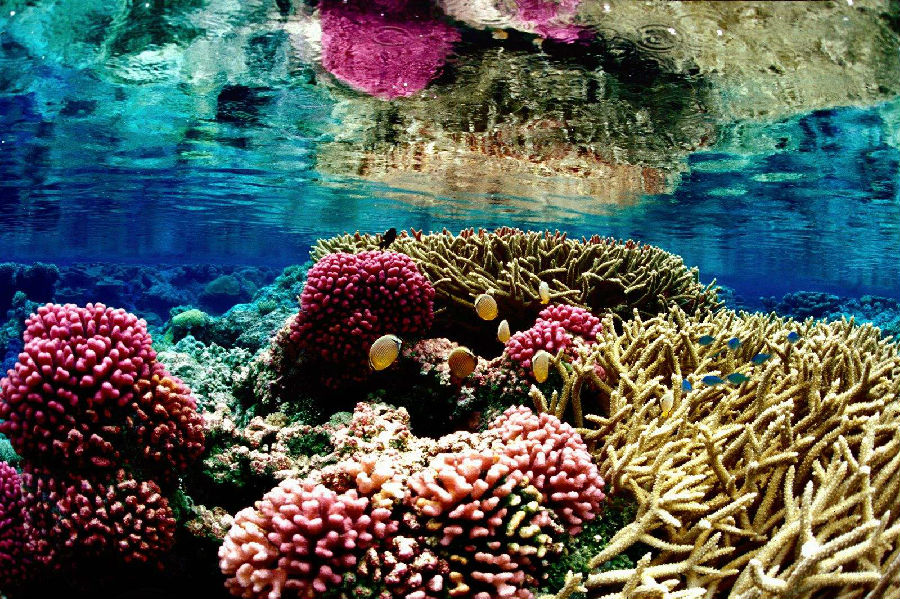

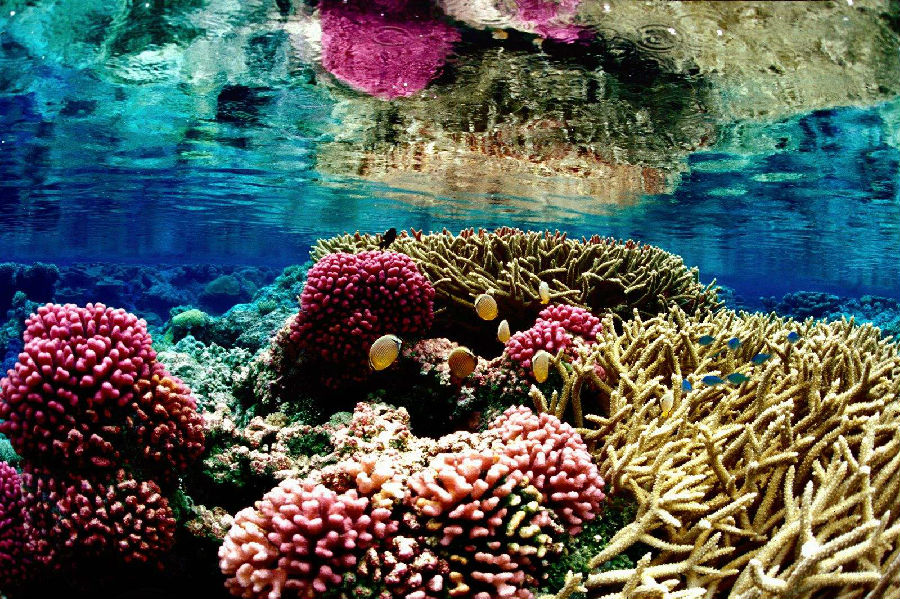

So why, if the seas are so vast, do we so easily overtax them? Well, to begin with, the world's seas are not uniformly bounteous. Altogether less than a tenth of the ocean is considered naturally productive. Most aquatic species like to be in shallow waters where there is warmth and light and an abundance of organic matter to prime the food chain. Coral reefs, for instance, constitute well under 1 percent of the ocean's space but are home to about 25 percent of its fish.

那么,既然海洋那么浩瀚,我们怎么就如此容易地弄得它负担过重了呢?首先,世界上的海洋并不都是很丰盈的。总共只有不足十分之一的海洋被认为天生很富饶。大多敖数的水生动物喜欢待在浅水里,那里有热量,有光线,还有丰富的有机物质来抚育食物链。比如,珊湖礁占了远不足海洋空间的1%,但那里是大约25%海洋鱼类的家园。

Elsewhere, the oceans aren't nearly so rich. Take Australia. With over 20,000 miles of coastline and almost nine million square miles of territorial waters, it has more sea lapping its shores than any other country, yet, as Tim Flannery notes, it doesn't even make it into the top fifty among fishing nations. Indeed, Australia is a large net importer of seafood. This is because much of Australia's waters are, like much of Australia itself, essentially desert. (A notable exception is the Great Barrier Reef off Queensland, which is sumptuously fecund.) Because the soil is poor, it produces little in the way of nutrient-rich runoff.

在别处,海洋根本没有那么富庶。以澳大利亚为例。这个国家拥有36735公里长的海岸线和2300万平方公里以上的领海,有着比任何别的国家更多的拍击海岸的海浪,然而,正如提姆·弗兰纳星指出的,它在捕鱼国家中还排不到前50位。实际上,澳大利亚是个海鲜的净进口国。这是因为澳大利亚的很大一部分水域,就像澳大利亚本身的很大部分一样,都是荒漠。(一个令人注目的例外是昆士兰近诲的大堡礁,那可是个极其富饶的地方。)由于土壤贫癖,它的径流里实际上不含任何营养。

Even where life thrives, it is often extremely sensitive to disturbance.

即使是生命很丰富的海域,也往往对于扰极其敏感。