您现在的位置:

首页 >

英语听力 >

双语有声读物 >

万物简史 >

正文

- By the middle of the nineteenth century most learned people thought the Earth was at least a few million years old,

- 到19世纪中叶,大多数学者认为地球的年龄起码有几百万年,

- perhaps even some tens of millions of years old, but probably not more than that.

- 甚至也许几千万年,但也很可能没有那么大。

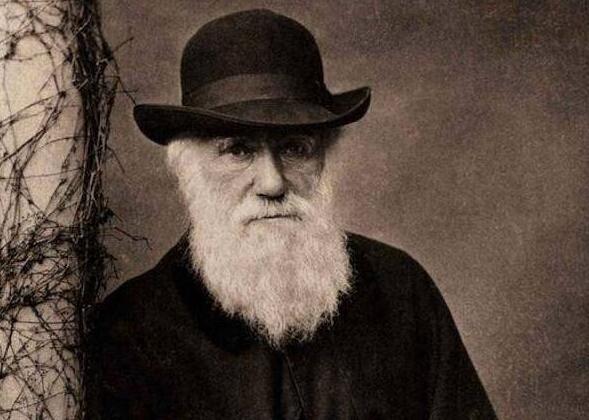

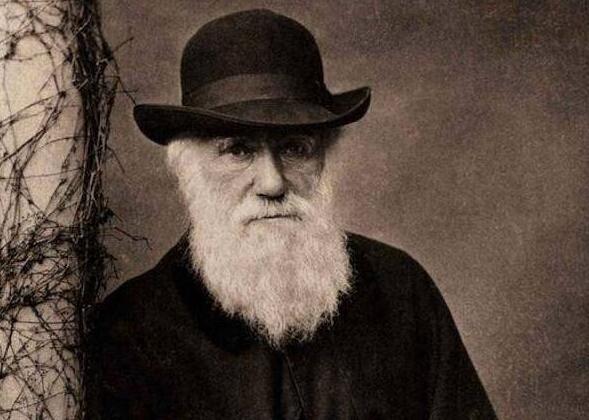

- So it came as a surprise when, in 1859 in On the Origin of Species,

- 因此,人们不由得大吃一惊,因为1859年查尔斯·达尔文在《物种起源》一书中宣称,

- Charles Darwin announced that the geological processes that created the Weald,

- 根据他的计算,创造威尔德地区

- an area of southern England stretching across Kent, Surrey, and Sussex, had taken, by his calculations,

- 英格兰南部的一个地区,包括肯特、萨里和苏塞克斯的地质进程

- 306,662,400 years to complete.

- 花了306662400年时间才完成。

- The assertion was remarkable partly for being so arrestingly specific

- 这个结论是很了不起的,部分原因是他说得那么确切,

- but even more for flying in the face of accepted wisdom about the age of the Earth.

- 但更因为是他公然不顾公认的有关地球年龄的看法。

- Darwin loved an exact number.

- 达尔文热衷于用精确的数字表达。

- In a later work, he announced that the number of worms to be found in an average acre of English country soil was 53,767.

- 在随后的一部著作中,他发表文章称英国农村的土壤中,每英亩可找到的蠕虫数量有53767之多结果,

- It proved so contentious that Darwin withdrew it from the third edition of the book.

- 它引起了激烈的争议,达尔文在该书的第三版中收回了他的看法。

- The problem at its heart remained, however. Darwin and his geological friends needed the Earth to be old,

- 然而,问题实际上依然存在。达尔文和他的地质界朋友希望地球很古老,

- but no one could figure out a way to make it so.

- 但谁也想不出办法。

扫描二维码进行跟读打分训练

扫描二维码进行跟读打分训练

By the middle of the nineteenth century most learned people thought the Earth was at least a few million years old, perhaps even some tens of millions of years old, but probably not more than that. So it came as a surprise when, in 1859 in On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin announced that the geological processes that created the Weald, an area of southern England stretching across Kent, Surrey, and Sussex, had taken, by his calculations, 306,662,400 years to complete.

到19世纪中叶,大多数学者认为地球的年龄起码有几百万年,甚至也许几千万年,但也很可能没有那么大。因此,当1859年查尔斯·达尔文在《物种起源》一书中宣称,根据他的计算,创造威尔德地区——英格兰南部的一个地区,包括肯特、萨里和苏塞克斯——的地质进程花了306662400年时间才完成时,人们不由得大吃一惊。

The assertion was remarkable partly for being so arrestingly specific but even more for flying in the face of accepted wisdom about the age of the Earth. Darwin loved an exact number. In a later work, he announced that the number of worms to be found in an average acre of English country soil was 53,767. It proved so contentious that Darwin withdrew it from the third edition of the book. The problem at its heart remained, however. Darwin and his geological friends needed the Earth to be old, but no one could figure out a way to make it so.

这个结论是很了不起的,部分原因是他说得那么确切,但更因为是他公然不顾公认的有关地球年龄的看法。达尔文热衷于用精确的数字表达。在随后的一部著作中,他发表文章称英国农村的土壤中,每英亩可找到的蠕虫数量有53767之多结果,它引起了激烈的争议,达尔文在该书的第三版中收回了他的看法。然而,问题实际上依然存在。达尔文和他的地质界朋友希望地球很古老,但谁也想不出办法。

来源:可可英语 http://www.kekenet.com/Article/201604/439472.shtml