GOING by the numbers, China’s notoriously hazardous coal mines have become less perilous in recent years. InJanuary the government said that 538 people had died in mining accidents in 2016, a mere 11% of the death toll a decade earlier. The total number of deathsper million tonnes of coal extracted was the lowest ever. For Chinese industry generally, safety data are improving. In 2002 140,000 people died inwork-related accidents; last year the toll was less than one-third as high. On roads there has been similar progress: 58,000 deaths in 2015, down from 107,000in 2004. Officials admit the statistics remain “grim”, but their efforts to improve safety are apparently paying off.

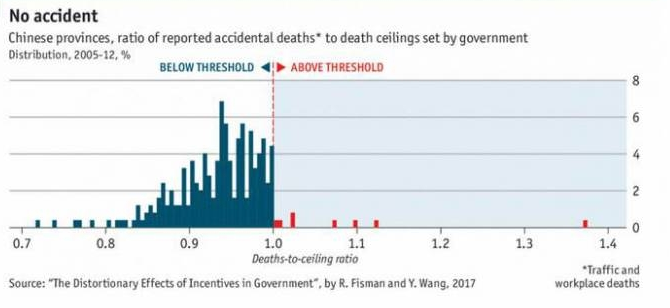

To see how the policy has worked,Mr Fisman and Mr Wang calculated the deaths-to-ceiling ratio (reported deaths divided by the mandated ceiling) for each province. Most provinces would be expected to be close to the target, with some slightly above and some slightly below.But almost all the ratios the scholars calculated were shy of 1 (see chart),with an abrupt fall-off in numbers once the ceiling is surpassed. This suggests fiddling: the cliff-edge looks suspicious, and it is highly unlikely that the government set the ceilings generously high. Safety standards, the authorsconclude, have not improved as much as the numbers seem to show.