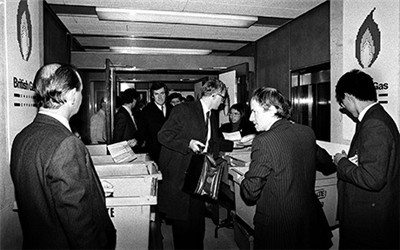

Last-minute subscribers deliver their applications for British Gas shares at one of the receiving banks, National Westminster, in the City of London. Photograph: PA/PA Archive/Press Association Images

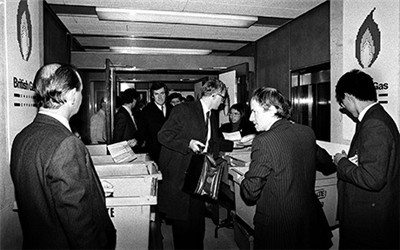

一家受理银行——伦敦市韦斯特敏斯特国家银行里最后一波申购英国石油公司股票的人。照片提供:PA/PA档案馆/联合摄影社

In the first stages of disillusionment, it didn't seem obvious to me to make connections between the extremes of marketisation and privatisation in the former Soviet Union and the partial privatisation of a British economy that had always been mainly private anyway. After all, where Britain had a series of regulators to set rules for the privatised industries – Ofcom, Ofwat and so on – the principal regulator of privatisation in Ukraine and Russia, at least in the early days, was murder. In Russia in particular, a small number of individuals quickly became fantastically rich when they took private control of state producers of petrochemicals and metals. They were grotesquely rewarded, or grotesquely undertaxed, and money that should have gone to rebuild roads or hospitals or schools went instead towards yachts, property in London and foreign football teams. But that had nothing in common with privatisation in Britain – did it?I began to notice something odd about the British and American business people and financial advisers I met in Ukraine and Russia in the 1990s. It was no surprise, I suppose, that they cared more about businesses being overtaxed than undertaxed, more about protection of private property than about protection of pensioners; that they didn't care how weak and bullied the local trades unions were. Besides, their Russian interlocutors kept being assassinated. What was revealing was how many of these emissaries of the capitalist way seemed to believe the myth that all that was good in the British and American economies had been constructed by the free market. They seemed to believe, or talked, made speeches, wrote papers as if they believed, that the entire structure of their own wealthy modern societies – the roads, the electricity grids, the railways, the water and sewage systems, the universal postal services, the telecoms networks, housing, education and health care – had been brought into being by individual entrepreneurs driven by desire for gain, with the occasional lump of charity thrown in, and that a bloated, parasitical state had come shambling onto the scene, seizing assets and demanding free stuff for its shirker buddies. I don't want to absolve the Russians or Ukrainians of responsibility for their handling of the aftermath of communism, but the template they were handed by the fraternity of the Washington Consensus was based on fake history. If this is what the triumphalists of Wall Street and the City of London told the Russians about the way of the capitalist world, I thought when I moved back to Britain in 1999, what have they been telling us? And what came of it?

在觉醒的最初阶段,我似乎并没有明显的将前苏联的极度市场化和私有化与主体一直保持私有制的英国的部分私有制经济联系在一起。毕竟英国拥有一些监管者为包括:ofcom、ofwat等在内的私有行业制定规则。而乌克兰和俄罗斯的基本监管者们,至少在最初阶段都是杀人凶手。尤其在俄罗斯,一小部分人将国有的石油和钢铁企业变为己有,迅速暴富。他们荒诞地接受奖赏,荒诞的逃避税收,并且将用来翻修道路、医院或学校的资金变成为自己购买游艇、伦敦的房产以及国外的足球俱乐部。但英国的私有化与这些有本质区别,对吗?我开始注意到90年代在乌克兰和俄罗斯遇到的英美商人和金融顾问们的一些奇怪的地方。我猜想,他们更在意公司的赋税过重而不是税赋减少,更关注于保护私有资产胜过退休金,这并不令人惊讶,因为他们并不在意地区工会有多强势或者软弱。除此之外,俄罗斯的内部人士总要防备暗杀。这揭示了如此众多的资本主义先行者似乎都相信英美建立在自由市场基础上的经济神话都是有益的。他们似乎相信,或者一直在说,在演讲,在撰写论文,仿佛坚信自身现代社会的根本架构为方方面面,包括:道路、电网、铁路、水利灌溉、全球邮政、电信网络、住房、教育、卫生等,带来富足。这些都源于追求利益的私人企业,间或还会向慈善机构供给些施舍,造成了一个臃肿的寄生状态,蹒跚上路,攫取财富并且为自己小团体创造利益。我不想免除俄罗斯或乌克兰人对社会主义余波的影响处理不当的责任。但他们抄袭的样板来自于达成华盛顿共识的各方,并基于一个虚假历史。如果这就是华尔街或伦敦城的胜利者们告诉俄罗斯人的资本主义世界的经验,那么我认为当我1999年回到英国够,他们还有什么要告诉我们呢?结果又会如何?

When Thatcher's Conservatives came to power in Britain in 1979, much of the economy, and almost all its infrastructure, was in state hands. Exactly what gloss you put on "in state hands" depends on your political point of view. For traditional socialists, it meant "the people's hands". For traditional Tories, it meant "in British hands". For Thatcher and her allies, it meant "in the hands of meddling bureaucrats and selfish, greedy trade unionists". How much of the economy? A third of all homes were rented from the state. The health service, most schools, the armed forces, prisons, roads, bridges and streets, water, sewers, the National Grid, power stations, the phone and postal system, gas supply, coal mines, the railways, refuse collection, the airports, many of the ports, local and long-distance buses, freight lorries, nuclear-fuel reprocessing, air traffic control, much of the car-, ship- and aircraft-building industries, most of the steel factories, British Airways, oil companies, Cable & Wireless, the aircraft engine makers Rolls-Royce, the arms makers Royal Ordnance, the ferry company Sealink, the Trustee Savings Bank, Girobank, technology companies Ferranti and Inmos, medical technology firm Amersham International and many others.

1979年撒切尔保守党上台时,英国大部分产业,几乎所有的基础产业都掌握在国家手中。确切的说,如何解释“掌握在国家手中”这句话取决于你的政治观点。对于传统的社会主义者,这意味着“在人民手中”;对于传统的保守派,意味着“在英国手中”;对于撒切尔及其盟友,意味着“掌握在玩弄权术的官僚和自私贪婪的行业协会手中”。到底有多少企业呢?三分之一的租赁房屋属于国有。卫生行业、大多数的学校、军队、监狱、道路、桥梁和街道、水利、排污、国家电网、发电厂、邮政电信、天然气、煤矿、铁路、废品回收、机场、很多港口、地方和长途客运、货运、核能源、空中航路、很多汽车、轮船、飞机制造厂、大多数钢铁企业、英国航空、石油公司、英国无线集团、飞机发动机制造商劳斯莱斯公司、武器制造商皇家军械集团、渡轮公司sealink、英国信托银行、吉尔银行、高科技公司、医药技术公司以及很多其他企业。

In the past 35 years, this commonly owned economy, this people's portion of the island, has to a greater or lesser degree become private. Millions of council houses have been sold to their owners or to housing associations. Most roads and streets are still under public control, but privatisation has reached deep into the NHS, state schools, the prison service and the military. The remainder was privatised by Thatcher and her successors. By the time she left office, she boasted, 60% of the old state industries had private owners – and that was before the railways and electricity system went under the hammer.

过去35年间,英国的这种广泛意义上的国有经济体,属于人民的英伦岛,或多或少变成了私有。数百万市政厅大楼被卖给他人或房屋中介机构。主要道路和街道仍旧公有,但私有化已经深入到NHS、公立学校、监狱设施和军队当中。剩下的被撒切尔及其后任进一步变卖。到她离任之际,她宣称60%的老旧国有企业已经转到私人名下,并且在此之前铁路和电力系统已经纳入私有轨迹。

The original background to Thatcher's privatisation revolution was stagflation, a sense of national failure, and a widespread feeling, spreading even to some regular Labour voters, that the unions had become too powerful, and were holding the country back. Labour, and Thatcher's centrist predecessors among the Conservatives, had tried to control inflation administratively, through various deals with unions and employers to hold down wages and prices; Labour had, under pressure from the IMF, cut spending. But Thatcher and her inner circle planned to go further, horrifying moderates in their party with the radicalism of their intentions.

撒切尔私有化改革的最初背景是由于经济不景气,全国上下充满失败情绪,人们普遍感觉工会掌握的权利太大,并且阻碍了国家的发展,这种感觉甚至蔓延到有些普通的工党支持者。工党和保守党中撒切尔的温和派前辈力图通过行政抑制通胀,通过与工会和雇主们达成各种交易来降低工资和物价。由于受到IMF的很大压力,工党削减了开支。但撒切尔和她的幕僚们计划要走得更远,他们雄心勃勃的激进主义思想令党内的中间派颇感震惊。

The late Alan Walters, her chief economic adviser, believed a key source of inflation and the weak economy was the amount of taxpayers' money being poured into overmanned, old-fashioned, government-owned industry. Just as in the Soviet Union, he thought, Britain's state industries concealed their subsidy-sucking inefficiency through opaque, idiosyncratic accounting techniques that took little account of how much time and effort were required to do and make things, or what people actually wanted to buy, or how much they were prepared to pay for it. As long as the subsidies kept coming, neither managers nor workers had much incentive to come up with smarter working methods or accept new technology, because that would mean fewer jobs, which would mean less power for the bosses and a smaller union. Yes, Walters knew, his protégée would slash spending on steel and coal and power and all the rest, yes, hundreds of thousands of workers would be sacked, but that wasn't enough. As many state-owned companies as possible must be privatised – be divided up into shares and sold to the public. They'd no longer be subsidised; they'd have to borrow money like any private company, account meticulously to shareholders for every penny they spent or earned, and strive to make a profit. The bigger the profit, the more efficiently the firm would be doing its job, and the more management would be rewarded. Most importantly, they'd have to compete with other firms. If they fell behind their competitors, they'd risk bankruptcy. Managers would face incentives for success and penalties for failure. British industry would become more competitive internationally. It would serve citizens better. Government would save the taxpayer money. The sacked workers would get redundancy payments; they'd go off and start businesses, or find other, more useful jobs once the economy was working properly. Everyone would win, except the lazy, and Arthur Scargill.

撒切尔的经济顾问,已过逝的沃特思先生相信通胀经济疲软的关键原因是纳税人的钱被用于人员臃肿、老式的国有企业。他认为就像苏联一样,英国的国有企业通过不透明、特殊的财务技巧掩盖了他们吸收补贴却毫无效率的行为,很少算计用于生产投入的时间和精力,人们真正的需求以及他们为此所付出的成本。只要补贴继续存在,无论是经理人还是工人都没有太多动力去研发更科学的方法或引进新技术,因为这将意味着工作岗位的减少,减少老板们和工会的权利。沃特思肯定清楚他的上司会向钢铁、煤炭、能源以及所有的其他产业挥舞大棒,减少支出,并且肯定会有成千上万的工人被解雇,但这些还都不够。由于必须尽可能的实现很多国有企业的私有化,将划分他们的股权,并转卖给公众。因此他们不再享受补贴,他们不得不像私有企业一样贷款,对支出斤斤计以保障股东们的投入物有所值,并且努力赚取利润。盈利越大,这些企业的工作越高效,管理层得到的汇报越高。最为重要的是,他们不得不与其他企业竞争。如果他们落后于对手,他们将面临破产危机。管理者面对的是成功的刺激和失败的惩罚。英国产业将变得更加具有国际竞争力,将更好的服务于国民。政府将节约税收。失业的工人将会得到补偿金,他们会离开并开启新的事业,或者一旦经济运转正常,他们会找到其他更有用的工作。每个人都会受益,除非是懒人和亚瑟萨卡吉尔一类的人。